Originally Posted by

Jim Kyle

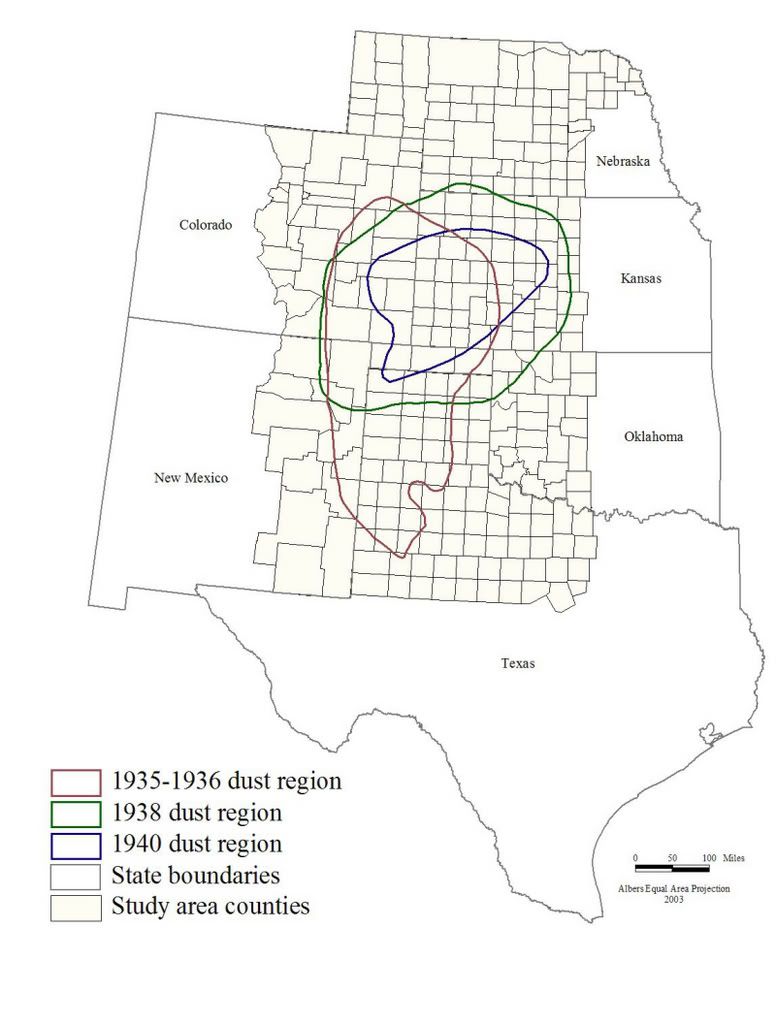

I suspect I may be one of a very few people participating here who actually lived through the dust bowl and had rather direct first-hand experience of its effects. For starters, the epicenter was NOT Texas, but southeastern Colorado!

One of the classic photos that has come to symbolize the Dust Bowl shows a young boy running to his house, which is half-buried in blown dust. Yes, it was taken in Oklahoma -- but it was in the Panhandle, not the main part of the state. And the dust came in from the north -- Colorado.

I spent the Dust Bowl years in Elk City, which was on the edge of the hardest-hit areas. My father was the area supervisor for the Forest Service's Plains State Forestry Project, popularly know as the ShelterBelt Project, which planted fast-growing trees along east-west section lines to serve as windbreaks and lift the blown dust into the air rather than let it bury productive topsoil. This project operated mostly in three states: Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska. Oklahoma was the southern end of its area, and only the counties in the western half of the state were included: Beckham, Custer, Greer, and Roger Mills were the ones with which I was most familiar as a youngster barely into my school years.

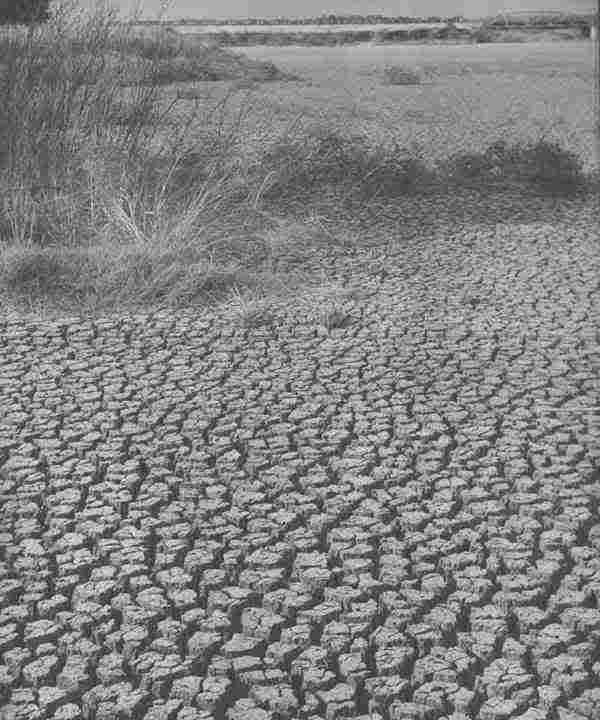

I remember only one major dust storm hitting Elk City during those years. It may have been 1935 or 1936, or even 1937 (the year I began first grade). It approached from the north, and lasted most of a day. However there were many "minor" storms that reduced visibility to a half-mile or so for several hours at a time, and to this day I dislike stiff winds and the yellow-sky look of blowing dust.

Today, almost none of the ShelterBelts still exist. The project ended in 1941, as the attention of the federal government turned toward defense preparation. However most of its personnel were called back in late 1942 to form the Emergency Rubber Project, which grew a variety of sagebrush that has higher-than-normal latex content. This bush, known as guayule, provided the seed molecules that enabled our nation to create synthetic rubber; we were told in 1945 that every B29 that flew was taking off on tires made possible by our guayule plants, although none of them reached full maturity before the war's end.

My family relocated to southern California on a 1,040-acre plantation between Beaumont and Banning, at the crest of the San Gorgonio Pass, in December of 1942. When I started school at Beaumont after the Christmas break, I was scorned as "another one of those damned Okies" and had to battle at every recess period. I'm sure none of the other students had read Steinbeck, but they certainly had a stereotype planted in their young minds.

And the worst dust storm I ever experienced happened on that guayule plantation between Palm Springs and L.A., in the spring of 1943. It reduced visibility to less than five feet -- but lasted less than a day, and its worst effects were limited to the plantation itself, which had been stripped of ground cover in preparation for planting the crop.

My only complaint with Steinbeck's work is that he failed miserably to do his research. Had he placed the Joads' farm in Roger Mills county, the desolation would have been quite believable -- and the folk there are still every bit as good as those from Little Dixie (where he did place their origin)...

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks